Last week I wrote about my paternal grandfather and his experiences during the First World War and also about my uncle Cyril during the Second World War. Now I want to write about the women on the home front and how they coped during these difficult times, especially both my grandmothers, Charlotte and Violet.

I can't imagine the immense wory that my Nana,Violet Orwin must have had when her 17 year old son joined the R.A.F. knowing the danger that he was in during every mission, I worried when my children where late home from an evening out. Then when the dreaded telegram arrived with the notification that he had been shot down, I am sure that her sadness and grief was unbearable and that even though it must have been a great relief to hear that he was still alive, to know that he had been taken as a prisoner by the enemy. Violet's husband, my Grandfather, Herbert Cyril Orwin was also called up to serve King and Country. Even though he was already in his forties my Grandfather was sent to serve in India. I am not sure exactly when he was called up to serve, I think that it was near the end of the war, but Nana was left to cope on her own.

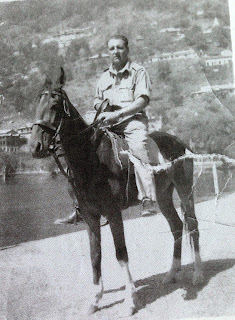

This is Herbert Orwin in India

My Mum Doreen Bertha Orwin was 13 when World War 2 broke out, this was a very worrying time and caused Doreen to breakout with psoriasis. With Hull being a big port it was very badly bombed during the war, Doreen’s family had an air-raid shelter in the back garden with bunks and bedding and food, but it was not very nice having to sleep there every night and hearing the sirens and the bombs falling. Doreen usually received the hand me down clothes from her elder sister Joan, but once during the war she had received a brand new strawberry pink coat, she was so proud of it that she had it hanging in the living room to show to some friends, when her father came to warn them of an air-raid, land mines hanging on parachutes were blowing in their direction. They rushed to the shelter, it was very frightening as they could see the land mines coming down, thankfully the wind blew them further down the street and one of them landed in Rokeby Park in a lot of mud, but it caused such a big crater you could have fitted three houses into it, and the explosion caused all the windows to blow in and the plaster to fall from the ceilings. Luckily everyone was in the shelter so no one was injured but Doreen’s new coat was covered with plaster and soot so she was most upset. The buzz bombs were also very frightening, they made a horrible shrill noise as they were passing overhead, but it was when they went still that you were most afraid as it meant that they were coming down. Once Doreen recalled sheltering under the table and her mother got angry with her because she thought she was playing with a torch, “stop playing with that torch” she said, but it wasn’t the torch but the flames coming out of the back of the buzz bombs. One of the reasons that the area in which Doreen lived was regularly attacked was because close by was a park in which there where two anti-aircraft guns, these guns were called Big Berthas and for this reason Doreen hated her middle name and would never tell anyone what the B was for.

Violet with daughter Joan and friend and Cyril in the background

My other Grandmother Charlotte was left alone with four young daughters under the age of 7 to look after while her husband was fighting for King and Country during the First World War. Hull being a an important Port made it a target for bombing, not just in the Second World War but also during the

First World War it regularly came under attack from zeppelin raids, there were at least 12 occasions when bombs fell on the city and air-raid warnings were more frequent because of zeppelins travelling over the city to other areas. My aunt Alice can remember several of these air-raids, often they would climb under the kitchen table until everything was clear though on one occasion she can remember her mother wrapping them in blankets and taking them out to a field where they had to lay in the snow with the blankets over them until the zeppelins had passed by, this could have been the 5th of March 1916 when two zeppelins attacked Hull during the night. Aunt Alice told me the following, “I remember the 1st World War, I was at school, I was born in 1911, and I started school during the war. I remember being at school when the buzzers (sirens) would go and mother would come and get us... We often went across the road to a neighbour - Mrs Thompson they called her, during the Great War the women wore ankle length black skirts and big white aprons, sometimes flat pancake hats on their heads, their hair in a bun. My father stopped my mother going over because Mrs Thompson used to get so excited when the bombs came over because next door to her there lived a German family and she used to get big lumps of coal and throw them over next door were the Germans lived and call them all sorts of things. When the bombs were dropping we used to go under the kitchen table and when she wasn’t looking we would pinch the sugar bowl and the tin of Bourneville cocoa and mix them together.”

I certainly feel a lot of love and respect for these strong and courageous women who were able to carry on in difficult times and where good Mothers to their children.